Over the last few months we’ve been putting posts and comments on twitter and Facebook about sheep wandering in the fells with a poem attached to them. Now that they’re back, it’s time to share a bit more of the story behind it.

Over the last few months we’ve been putting posts and comments on twitter and Facebook about sheep wandering in the fells with a poem attached to them. Now that they’re back, it’s time to share a bit more of the story behind it.

Over the years, the land has seeped into our work. It’s a kind of muse, you could say, and its essence and energies fuel the words on the page and the composition and mood of photographs.

This goes part way, but doesn’t directly explain why a bunch of sheep ended up wandering the fells with words stitched onto them. That was more to do with curiosity: what would happen to a poem if it entered the land and moved with the sheep?

On one level, this is simply a poem. But in fact, it was no ordinary poem: its journey would never be ordinary.

On one level, this is simply a poem. But in fact, it was no ordinary poem: its journey would never be ordinary.

The kinetics of the thing

The kinetics of the thing

Moving, always. From mind to paper to cloth to barn to hand to sheep to fell – through bog and grass and rock, crag, beck and scree to skyline – from fell to intake to yard to barn to hand.

The temporality of the thing

Once in place, stitched onto the back of the sheep, the poem was dispersed, changed, never to be in order again. Its flow in the land would be unwitnessed, uncontrolled, unknown, pushed by spaces, weather, hunger, a need for shelter.

We went to search for the sheep. We didn’t find them.

On the fell, the spaces between the words on the sheep spoke. We were walking between its words, reading the land and the weather through our own footsteps. All was visual, visceral, relational, temporal. Above us, the sky, a vast, borderless white space, momentarily held the punctuation of a raven.

A few weeks later, we set out a second time to find the sheep. Again, we did not. The white space we encountered this time was snow. The poem was able to declare itself once again, word by word, as I inscribed sections of it into a natural canvas.

A white space. My mind. The sky. Paper. Snow. Clouts. Sheep. A poem, arising, finding form, settling, dispersing, disappearing, waiting, intrinsically linked with its environment.

After three months on the fell, it was time for the farmers to bring the flock in. On the first day we brought in around 300 sheep. The first word we spotted was ‘caught’. Another two days were needed to gather in the remainder of the thousand-strong flock. The clouted sheep were separated and left in the intakes while the pregnant ewes were scanned. A week later, on a grey morning, 350 sheep with clouts stitched over their tail ends were gathered down to the valley and brought into the yard. Twenty carried words.

After three months on the fell, it was time for the farmers to bring the flock in. On the first day we brought in around 300 sheep. The first word we spotted was ‘caught’. Another two days were needed to gather in the remainder of the thousand-strong flock. The clouted sheep were separated and left in the intakes while the pregnant ewes were scanned. A week later, on a grey morning, 350 sheep with clouts stitched over their tail ends were gathered down to the valley and brought into the yard. Twenty carried words.

The poem was a jostling of words in the midst of the wordless, a reconfiguration of thoughts, a half-seen phrase that never remained still. The sheep were urged, in groups of 30-40, into a small pen to have their clouts removed, and I worked with the farmer to cut them away.

The poem was a jostling of words in the midst of the wordless, a reconfiguration of thoughts, a half-seen phrase that never remained still. The sheep were urged, in groups of 30-40, into a small pen to have their clouts removed, and I worked with the farmer to cut them away.

Those with words, we put to one side. They stood against the back wall of a half-lit barn. As each one was sent through, I noted it, and in the course of a few hours, the rejigged poem filtered through. Only 19 of the 20 poem sheep came in (‘in a’ was still out there):

into land, twinter’s eye

future in the stitched

turned out bloodlines flow to the fell

hands, dogs, past

barn’s skyline folded, half-light in flock

caught

The poem clouts were removed, one by one, by knife and hand, by the farmer who had been instrumental in their original attachment. Full circle. Then the poem changed again, discarded but not dispersed, lying in a pile, in the order in which it had been cut away.

bloodlines flow

barn’s hands turned out in future

in the past, folded skyline

stitched present into land

dogs caught twinter’s eye

to the fell flock

half-light

The experience of the thing

The experience? Excitement, curiosity; challenge in the writing; destabilisation and sense of loss when the poem was let out to the fell; unexpected lack of disappointment at never seeing them again, until the gathering day; deeply sensual – the aroma of sheep and barn, needle through wool, rain-filled air, fell under foot, sky overhead, shepherds’ call on the breeze, knife cutting through stitches, my leg on sheep flanks, their heads on my thighs, dogs’ breath.

Meanings, attachment, and flow

In writing the poem I wanted to convey the sense of landscape, history, working the land, flock, ancestry and knowledge. Beyond that, I had no attachment to what happened once it was on the sheep.

I knew it would reorder itself, and I was curious about (but never fixated on) the ways it might do this. I was more interested in its form as a scattered poem: how the poem’s voice was affected by the isolation of its parts, how it would be affected by the weather, how it might be witnessed (or not), and by whom, and, if not witnessed, how others might lend their own interpretations about it even though they had not had any contact with it. All these questions could be applied to an upland flock of sheep, or to a community of farmers.

Any variations on the original order were out of human control, yet some pairings or phrases that appeared did seem to hold their own meanings, such as ‘turned out bloodlines to the fell’. The stitching and unstitching of the poem was an integral part of the process, just as the stitching of clouts on young ewes helps to maintain their health and supports the wellbeing of a flock. The reformations of the poem echoed this: ‘future in the stitched’ and ‘stitched present into land’.

The poem always had its own life, its own flow, vitality. Its expression on cloth, on sheep, was integral to its identity, and its ultimate end in a pile smelling of lanolin, shit and rain, is part of that. It is flow, it is in flow; just as the flow of sheep through land and sorting pens and hands is part of the nature of farming life in the fells.

A little bit of background information …

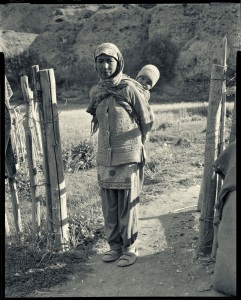

Herdwicks and Swaledales reared on the fells are best left until their third year before carrying a lamb. When they overwinter on the fells the shearlings (one year old, having had one shear) and twinters (having had two winters) are given protection in the form of a cloth (clout) sewn over their tail end. It’s not a widespread practice, but it has been used for centuries. It’s intensive, in terms of time and effort, but very effective. If a shearling or twinter falls pregnant the likelihood is that that sheep will never reach its full potential.

Clouting is an essential tool for many farmers. Even if they don’t put their own tups (rams) out to the fell, there’s no knowing if another tup might wander up there – the sheep are on common land where flocks from several farms graze over the winter. And there are often tups that are meant to be in enclosed land, but take a leap over the wall. A clout protects against this. The sheep that unwittingly carried a poem over winter were clouted in December 2014.

Clouting is one of the ways you ensure your current flock remains strong and the bloodline remains strong with it. Sending a poem out on the clouts was a way of emphasising the way farming wisdom is stitched both into the flock and into the land, the importance of protecting blood lines, and the cyclical nature of farming, both from year to year and from generation to generation. I wanted to capture the skill and movement of farmers over the land as they work with their flocks, as well as the landscape. It took a long time to come up with a poem that felt right in its entirety and would also withstand separation on the fell – and would sit well on the 20 clouts I was given.

The release of a poem has been possible thanks to the generosity of some farmers we know, and has come about in the wider context of my postgraduate research through the University of Glasgow, where I am doing a practice-led MPhil in Creative Writing : ‘Writing in Place’ Upland farming and its place within the cultural landscape of the Lake District, explored through poetry and prose. Some time during in the next wee while I’ll be posting a link to my evolving observations, poetry and analysis.

Rob has been a constant part of the process alongside me (even helped stitch some of the patches on the clouts) and all the photos are his.

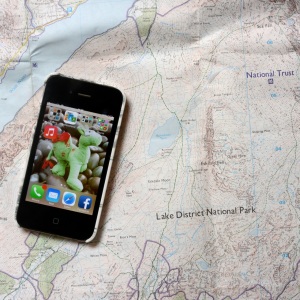

Wherever we go, almost without exception, we have impacted and affected the natural world – buildings, roads, plastics, mobile phones, (and frequent tweeting or blogging as I am doing now), cameras, maps, Google maps, GPS , radio waves … The list goes on.

Wherever we go, almost without exception, we have impacted and affected the natural world – buildings, roads, plastics, mobile phones, (and frequent tweeting or blogging as I am doing now), cameras, maps, Google maps, GPS , radio waves … The list goes on. We could even be romantic about the Anthropocene – well maybe optimistic is a better word. The naming of the Anthropocene recognises that human life is not so much about encountering our environment, but really about being part of it – being in our invironment. And yet there really is no change there, between 2015 and the eighteenth century when Thomas Gray was writing, and Wordsworth too (remember it wasn’t all prettiness and daffodils – he was concerned with the French Revolution, the abolition of slavery, and pollution and held dreams of pantocracy in his own imagined form of utopia).

We could even be romantic about the Anthropocene – well maybe optimistic is a better word. The naming of the Anthropocene recognises that human life is not so much about encountering our environment, but really about being part of it – being in our invironment. And yet there really is no change there, between 2015 and the eighteenth century when Thomas Gray was writing, and Wordsworth too (remember it wasn’t all prettiness and daffodils – he was concerned with the French Revolution, the abolition of slavery, and pollution and held dreams of pantocracy in his own imagined form of utopia). Call me an optimist, or even a romantic, but the Anthropocene is not simply a time to begin the countdown to devastation – it is an opportunity to harvest the knowledge we have about what hurts and what heals, and aim for some open-eyed living within the invironment that the whole planet shares .

Call me an optimist, or even a romantic, but the Anthropocene is not simply a time to begin the countdown to devastation – it is an opportunity to harvest the knowledge we have about what hurts and what heals, and aim for some open-eyed living within the invironment that the whole planet shares .